Flashback to the mid-1990s: Vanilla Ice released “Ice Ice Baby;” Ross and Rachel were on a break; and Google, Amazon, and Hotmail (RIP) graced the internet. Oh, the memories. At the same time–and connected to accelerating internet technologies like Google–a digital gap began to emerge.

As personal computer and internet access became readily available, there was also an observed disparity between access to technology and socioeconomic status. Scholars, policy makers, and advocacy groups referred to this as the “digital divide.”

What is the Digital Divide?

The digital divide refers to the gap between individuals, households, and communities that have access to modern information and communication technologies (ICTs) and those that do not. This divide can manifest in various ways, including differences in access to high-speed internet, computers, and digital literacy skills.

The digital divide is not just about technology access; it also encompasses disparities in the ability to use digital tools effectively, which can significantly impact opportunities for education, employment, and social engagement. For students, this gap can lead to inequities in learning experiences, academic performance, and future career prospects, as those without adequate digital resources may struggle to keep up with their peers.

Introducing the New Digital Divide

Today, more than 99 percent of K12 public schools in the US are connected to the internet, in large part thanks to the Federal Communications Commission’s congressionally mandated “E-Rate” program, which went into effect in 1998. As part of this program, schools must prove they comply with CIPA to qualify for E-Rate. Learn more on this blog about CIPA compliance.

School districts continue to spend billions each year on hardware, broadband, maintenance, and EdTech software. Though broadband use and school hardware availability are at an all-time high, a new digital divide has appeared. This is despite the myth that the ubiquity of cellphones, social media and other online platforms in students’ daily lives means students are digitally adept at navigating complex technology landscapes. Indeed, many students still do not have the basic technology skills they need for success in school and in their future careers.

Lagging technology skills haunt students as they move between grades and schools. Moreover, if students don’t develop a strong foundation with technology starting in elementary school, the digital divide will only widen as they continue in school. If students enter high school or college without proper technology skills, they will not be able to meet the expectations of their classes, such as using word processing and spreadsheet programs, conducting research to identify credible online sources, and typing notes at the speed of a garrulous professor’s lecture.

In the following sections, we will explore some key statistics that highlight the extent of the digital divide among students. These statistics will shed light on how the divide affects different demographics, regions, and educational outcomes. By understanding these figures, we can better grasp the challenges that students face and the importance of bridging the digital divide to ensure equal opportunities for all.

The First Digital Divide: Access and Connectivity

The Divide in Access:

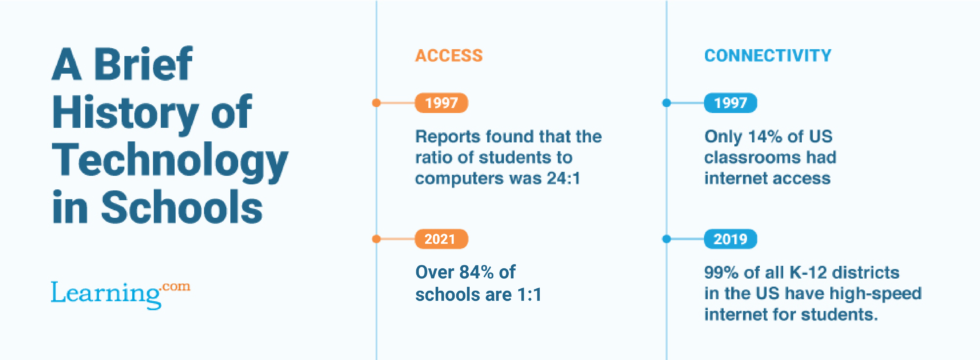

In 1997, reports found that the ratio of students to computers was 24:1. By 2017, over 50% of educators reported that their school is 1:1. But the COVID-19 pandemic created an urgent need for districts to provide devices to students. By March 2021, 90% of districts were 1:1 for their middle and high school students, and 84% were providing 1:1 for their elementary students, too.

The Divide in Connectivity:

Only 14 percent of US classrooms had internet access in 1997. But in 2019, EdWeek research confirmed that 99 percent of all K-12 districts in the United States have high-speed internet with 100 kpbs for students.

Digital inequity persists with ensuring connectivity in family homes, public libraries, and other after school gathering areas.

Access and Connectivity Beyond the School Walls

According to recent surveys:

- 87 percent of households had a desktop or laptop (source).

- 85 percent had a smartphone.

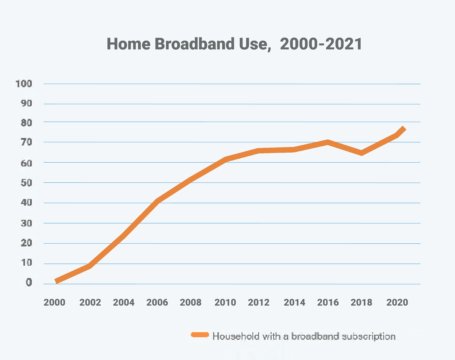

- 77 percent had a broadband subscription.

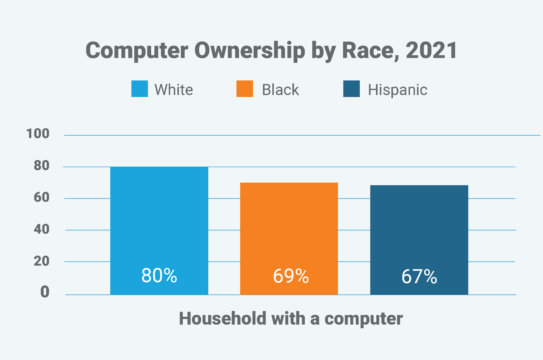

Example 1: Computer Ownership and Broadband Subscription Rates by Race

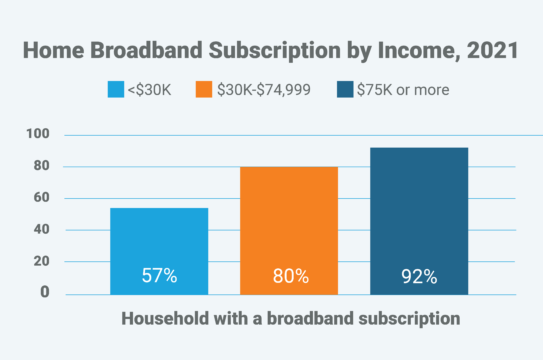

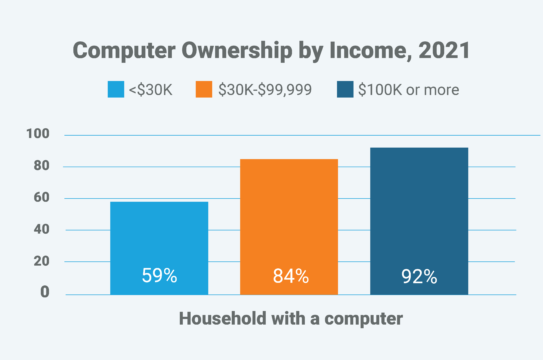

Example 2: Computer Ownership and Broadband Subscription Rates by Income

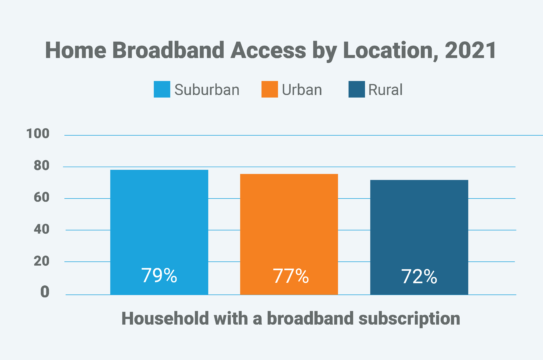

Example 3: Computer Ownership and Broadband Subscription Rates by Location

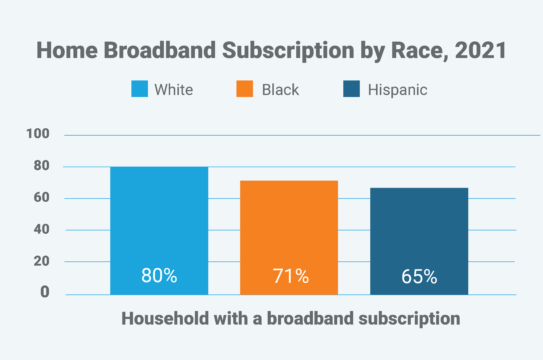

The takeaway is fairly simple: access and connectivity rates are impeded by long standing inequities in society that affect traditionally underserved minorities, low-income families and those residing in rural areas.

The Access and Connectivity Divide & Equity

The persistence of the access and connectivity divide, which runs in parallel with learning that depends upon access to devices and connectivity to the internet, further alienates students who are already underserved and disadvantaged.

The Second Digital Divide: Digital Readiness

A report from the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, quantified this divide among adult Americans:

- 13 percent of U.S. workers have no digital skills

- 18 percent of American adults have at best limited digital skills

- 35 percent of American workers have proficient digital skills

- 33 percent of U.S. adults are considered to have advanced digital skills

In general in the workforce:

- Demand for digital skills is increasing across industries

- Job growth is stronger in jobs that require more digital skills

- The more highly digitalized industries have faster-growing wages

But What About Digital Natives?

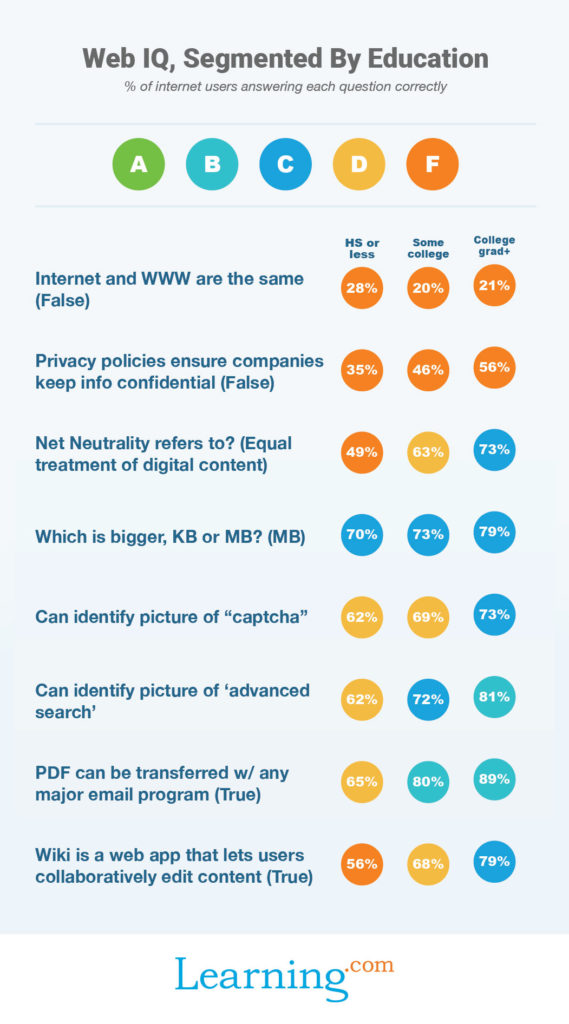

In a separate study by Pew, researchers surveyed adult Americans to gauge their Web IQ:

Findings:

- Age isn’t an accurate predictor of digital readiness.

- Education tends to be an accurate predictor.

Why does this matter? The digital native narrative often overlooks and even perpetuates the digital readiness divide among youth, according to research by Paul A. Kirschner and Pedro De Bruyckere.

The Digital Readiness Divide & Equity

Students who lack access and connectivity, whether in school or at home, have less experience using technology and are likely to have families with less experience. The digital readiness divide, in this context, is more likely to impact non-white, impoverished, and rural students, which preys on already existing inequity.

The Third Digital Divide: Digital Use

The digital use concerns the nature of technology integration in student learning.

Technology Use in the Classroom

The Digital Use Divide and Equity

A study by Connected Learning Alliance found that students in higher-income schools experienced technology as a creative and playful medium while those from middle and lower-income schools used it at a far more basic level.

A second report also uncovered that lower-income, non-white children were more likely to use technology for drill and practice compared to their more affluent peers, who used technology in learning for problem solving and higher-order thinking.

The Fourth Digital Divide: Representation

The fourth digital divide, as featured in our digital equity whitepaper, is in reference to representation in the learning content, technology industry, and computer science workforce.

In order to feel a sense of belonging, connection to the curriculum, and empowerment to pursue advanced academics and employment in technology, diversity and representation are necessary.

In an article by Kevin Clark in the Journal of Children and Media, he explains:

“The digital divide will not be truly closed until the content available reflects the full spectrum of our experiences and perspectives, so that fathers and mothers of all hues and demographic categories have access to books, videos, websites, and a whole host of media created by and containing characters who look like their daughters and sons.”

Especially in STEM and computer science contexts, special considerations need to be made to ensure that learning represents all students, even when the fields may lag in this.

A Computer Science Case Study

To illustrate the lack of diversity and representation, the following section examines the computer science field as an example. In the industry:

This lack of representation impacts us all.

Pipeline Build:

- In 2020, unfilled computer science positions reached over one million.

- Computer science jobs are expected to grow 22% by 2030 – much faster than average

- Only eight percent of college graduates in STEM elect to major in computer science.

Technology Accessibility:

- Speech recognition software with smart speakers is more likely to understand men than women, and the same is true for people with accents.

- Another example is that facial recognition software repeatedly fails to recognize women and people of color, which again is in part due to the gender and race of those designing it.

Wealth Gaps:

- Greater equity in the computer science workforce will also help to close gender and racial wealth gaps by enabling these groups to access higher incomes that empowers them, their family and their community.

In Support of Representation

It’s essential that all students have access to computer science and technology-driven learning experiences.

A study by Computer Science Education Week found that the likelihood women will major in computer science increases tenfold when they are enrolled in AP Computer Science. And Black and Latinx students are seven times more likely to major in it.

Beyond reaching younger students, progress will also require that curriculum be inclusive and representative.

In summary of all this data, Michele Knobel and Leeann Stone in the Educational Policy Journal explain:

“There is no single digital divide in education but rather a host of complex factors that shape technology use in ways that serve to exacerbate existing education inequalities.”

Obstacles to Teaching Technology Skills

Two common barriers to providing students with quality digital literacy instruction are inadequate teacher training and the lack of a standardized curriculum at most schools. Compared to core curriculum areas, teachers are often not provided specific training on teaching technology skills or any sort of curriculum to follow.

When this happens, teachers are essentially required to create their own curriculum by sifting through thousands of online resources. Vetting the quality and grade appropriateness of these items and creating lessons from scratch is laborious and time-consuming. As a result, students may encounter uneven quality of instruction.

Supported Teachers Lead to Equitable Instruction

In an effort to tackle this technology skills gap, many states have adopted national standards or created their own state standards that require specific technology skills be addressed within core subject areas.

For this to be effective, districts need to provide teachers with training, which includes best practices for using technology in the classroom, technology implementation models to follow, and clear guidelines for teaching technology skills, as well as a standardized curriculum for use across the district and ongoing support. When teachers feel included in the discussion about the role of technology in their school and are provided with the right support, they will feel empowered to introduce new concepts to their students.

This article was originally published by Learning.com in October 2020. Data and information have been updated to reflect current trends. The article was updated in October 2024 for additional information and relevance.

Learning.com Team

Staff Writers

Founded in 1999, Learning.com provides educators with solutions to prepare their students with critical digital skills. Our web-based curriculum for grades K-12 engages students as they learn keyboarding, online safety, applied productivity tools, computational thinking, coding and more.

Further Reading

Overlooked Digital Skills Students Need to Thrive in a Digital World

As the digital landscape continues to evolve at a rapid pace, educators, parents and policymakers are increasingly focused on preparing students for...

Creating a Classroom Guide to “Netiquette”: Promoting Respectful Online Behavior

In today’s digitally connected world, the importance of teaching students how to conduct themselves online has never been greater. The term...

Online Safety Definition & Basics

In today’s digital age where students are more connected than ever, online safety has become an important part of digital literacy education. With...